Mary Oliver is well known among the American’s best selling poets of age due to her lyrical, sensitive, and intimate poems, which are considered a mirror to reflect human’s most profound emotion out of joyful and joy to despair and sorrow.

Her poem’s best aspect is that they encourage readers not to take anything for granted and reminds us to breathe and sense the encompassing atmosphere (take a break for slower residing). If you would like to experience that grateful emotion, then allow Penn Book to give you a hand for nearer to the best Mary Oliver Poems below.

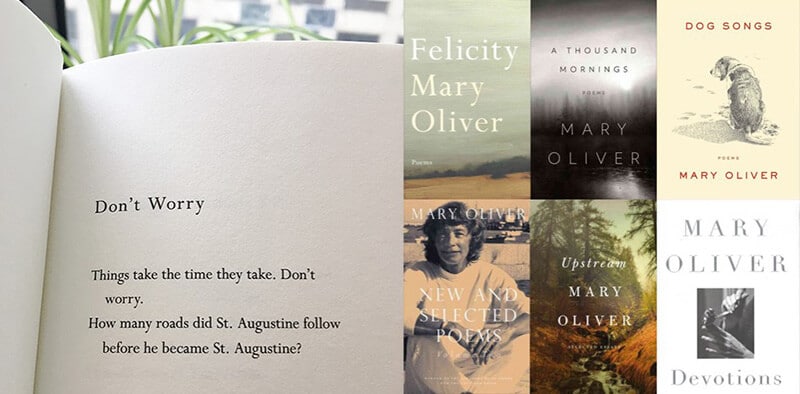

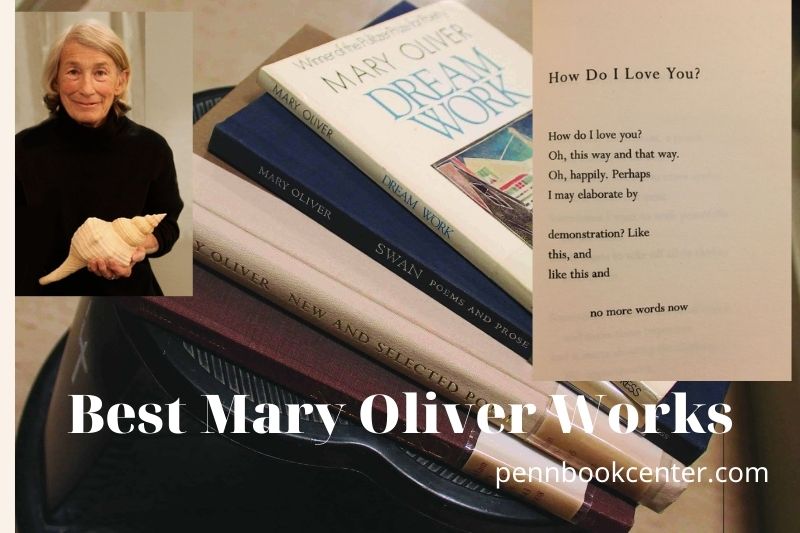

Mary Oliver and Her Poems

Mary Oliver is a famed American poet and non-fiction writer. They won the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award for her job American Primitive and House of Light, respectively. According to the New York Times, she’s far and away, the country’s best selling poet.

Mary Oliver’s poems often focus on themes of nature, spirituality, and the beauty of the everyday. They often feature vivid descriptions of nature and animals, as well as reflections on life, death, and the power of love.

Her poetry is often considered to be both accessible and contemplative, encouraging readers to slow down and appreciate the simple things in life.

Zoom through those inspirational quotations from many of the most important poets in our creation and possibly get a few admirations with this particular gift of the god known as character.

10 Best Mary Oliver Works about Life and Death, Love, Heavy

1. “Wild Geese”

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

Why we love this poem: If you have ever believed the world was falling to you, this poem acts as a relaxing reminder to associate with yourself, with character, and others about you. Oliver’s picture of geese in flight is intended to lift the reader and carry them from any grief and isolation they may be feeling.

2. “The Swan”

Did you too see it, drifting, all night, on the black river?

Did you see it in the morning, rising into the silvery air –

An armful of white blossoms,

A perfect commotion of silk and linen as it leaned

into the bondage of its wings; a snowbank, a bank of lilies,

Biting the air with its black beak?

Did you hear it, fluting and whistling

A shrill dark music – like the rain pelting the trees – like a waterfall

Knifing down the black ledges?

And did you see it, finally, just under the clouds –

A white cross Streaming across the sky, its feet

Like black leaves, its wings Like the stretching light of the river?

And did you feel it, in your heart, how it pertained to everything?

And have you too finally figured out what beauty is for?

And have you changed your life?

Why we love this poem: The swan in this poem is a type of shapeshifter. It could be soft and lovely like lace or flower petals or unpleasant and relentless like a waterfall. The poem reminds us that change is a natural part of life, and the last point is a challenge to the reader: What form are you going to choose?

3. “Don’t Hesitate”

If you suddenly and unexpectedly feel joy,

don’t hesitate. Give in to it. There are plenty

of lives and whole towns destroyed or about

to be. We are not wise, and not very often

kind. And much can never be redeemed.

Still, life has some possibility left. Perhaps this

is its way of fighting back, that sometimes

something happens better than all the riches

or power in the world. It could be anything,

but very likely you notice it in the instant

when love begins. Anyway, that’s often the

case. Anyway, whatever it is, don’t be afraid

of its plenty. Joy is not made to be a crumb.

Why we love this poem: Sometimes, it can be not easy to bask in an instant of happiness, particularly when you’re convinced that the atmosphere will not last. The poem admits this and urges the reader to capture every minute of pleasure and possibility and enjoy it regardless of how small!

4. “Dogfish”

You don’t want to hear the story

of my life, and anyway

I don’t want to tell it, I want to listen

to the enormous waterfalls of the sun.

And anyway it’s the same old story

a few people just trying,

one way or another,

to survive.

Mostly, I want to be kind.

And nobody, of course, is kind,

or mean,

for a simple reason.

And nobody gets out of it, having to

swim through the fires to stay in

this world.

Why we love this poem: This suggestion is about the other hand, so we’ve just included a snippet, but we invite you to see it in its entirety! Oliver brilliantly weaves the dogfish picture into a poem about living the past and the harsh realities of the planet.

Take a look at our Top 59 Best Poetry Books Of All Time: Top Pick Of 2024 to learn more about the greatest poetry publications all around the world.

5. “When Death Comes”

When death comes

like the hungry bear in autumn;

when death comes and takes all the bright coins from his purse

to buy me, and snaps the purse shut;

when death comes

like the measle-pox

when death comes

like an iceberg between the shoulder blades,

I want to step through the door full of curiosity, wondering:

what is it going to be like, that cottage of darkness?

And therefore I look upon everything

as a brotherhood and a sisterhood,

and I look upon time as no more than an idea,

and I consider eternity as another possibility,

and I think of each life as a flower, as common

as a field daisy, and as singular,

and each name a comfortable music in the mouth,

tending, as all music does, toward silence,

and each body a lion of courage, and something

precious to the earth.

When it’s over, I want to say all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.

When it’s over, I don’t want to wonder

if I have made of my life something particular, and real.

I don’t want to find myself sighing and frightened,

or full of argument.

I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world.

Why we love this poem: This poem faces death head-on with beauty and elegance, fulfilling it not with dread but with fascination. This poem’s speaker is not paralyzed by a fear of passing but sees it as a phone to experience everything that life has to offer you. The point about being a bride married to amazement never fails to move me.

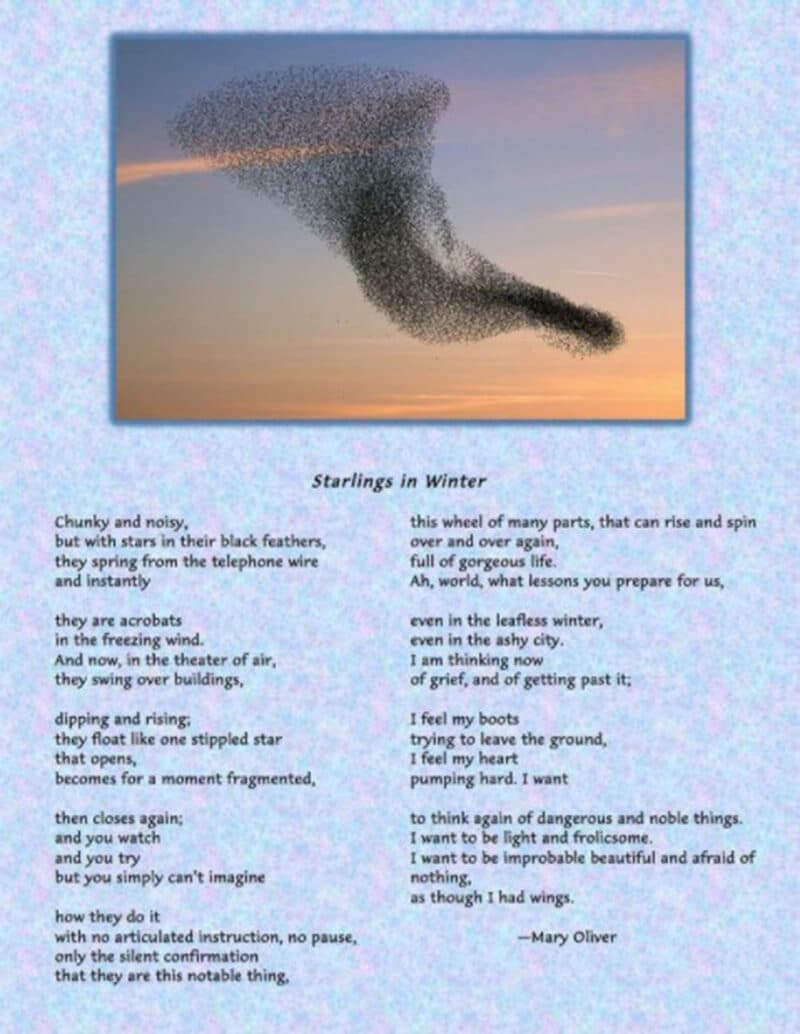

6. “Starlings in Winter”

Chunky and noisy,

but with stars in their black feathers,

they spring from the telephone wire

and instantly

they are acrobats

in the freezing wind.

And now, in the theater of air,

they swing over buildings,

dipping and rising;

they float like one stippled star

that opens,

becomes for a moment fragmented,

then closes again;

and you watch

and you try

but you simply can’t imagine

how they do it

with no articulated instruction, no pause,

only the silent confirmation

that they are this notable thing,

this wheel of many parts, that can rise and spin

over and over again,

full of gorgeous life.

Ah, world, what lessons you prepare for us,

even in the leafless winter,

even in the ashy city.

I am thinking now

of grief, and of getting past it;

I feel my boots

trying to leave the ground,

I feel my heart

pumping hard. I want

to think again of dangerous and noble things.

I want to be light and frolicsome.

I want to be improbable beautiful and afraid of nothing,

as though I had wings.

Why we love this poem: Oliver frequently turned into nature to meditate on mortality and life. This poem reminds us that grief is a process, which one step in that process is expecting the conclusion of despair. The understanding that happiness is possible could be its type of relaxation.

Read more about 12 Best Nikki Giovanni Poems To Read Of All Time to know more about this most renowned living antique works.

7. “The Summer Day”

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean—

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down-

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

Why we love this poem: This poem perfectly melds the religious and the organic, reminding the reader that life is valuable and worth living, even at its lowest and easiest moments.

8. “Praying”

It doesn’t have to be

the blue iris, it could be

weeds in a vacant lot, or a few

small stones; just

pay attention, then patch

a few words together and don’t try

to make them elaborate, this isn’t

a contest but the doorway

into thanks, and a silence in which

another voice may speak.

The reason why we love this poem:” In an interview with NPR, Oliver emphasized when it comes to poetry, simplicity would be most extraordinary: “Poetry, to be known, should be apparent… It should not be elaborate. I have the impression that a lot of poets are writing today, kind of tap dancing through it. I feel that anything that is not necessary shouldn’t be from the poem”. We believe this poem is an ideal illustration of precisely what she intended.

9. “The Uses of Sorrow”

(In my sleep I dreamed this poem)

Someone I loved once gave me

a box full of darkness.

It took me years to understand

that this, too, was a gift.

Why we love this poem: When it comes to feelings such as grief and despair, it may frequently be tough to get the appropriate words to say how you are feeling. This poem admits the constraints of speech, but it is also proof of its power. I am constantly in awe of brief poems which are able to comprise so much.

Have you ever looked for an excellent friend poem? If yes, read Best Poems About Friendship to heat your heart or even transfer yours to act at the moment.

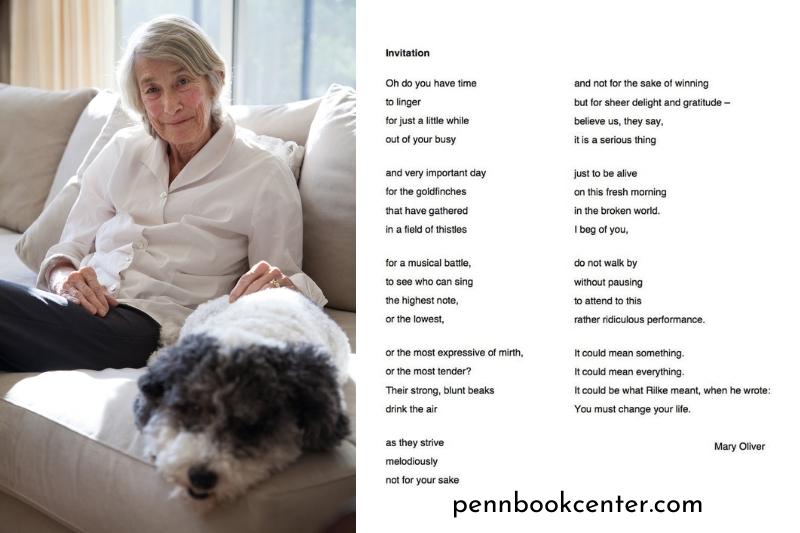

10. “Invitation”

Oh do you have time

to linger

for just a little while

out of your busy

and very important day

for the goldfinches

that have gathered

in a field of thistles

for a musical battle,

to see who can sing

the highest note,

or the lowest,

or the most expressive of mirth,

or the most tender?

Their strong, blunt beaks

drink the air

as they strive

melodiously

not for your sake

and not for mine

and not for the sake of winning

but for sheer delight and gratitude

believe us, they say,

it is a serious thing

just to be alive

on this fresh morning

in the broken world.

I beg of you,

do not walk by

without pausing

to attend to this

rather ridiculous performance.

It could mean something.

It could mean everything.

It could be what Rilke meant, when he wrote:

You must change your life.

Why we love this poem: Particularly nowadays, it may feel like there’s an infinite supply of distractions. Oliver’s suggestion is a call to listen, particularly to the things you take for granted. If we pause for an instant, even for something as inconsequential as a couple of birds singing, we may discover unexpected joy.

11. Coming home

When we are driving in the dark,

on the long road to Provincetown,

when we are weary,

when the buildings and the scrub pines lose their familiar look,

I imagine us rising from the speeding car.

I imagine us seeing everything from another place–

the top of one of the pale dunes, or the deep and nameless

fields of the sea.

And what we see is a world that cannot cherish us,

but which we cherish.

And what we see is our life moving like that

along the dark edges of everything,

headlights sweeping the blackness,

believing in a thousand fragile and unprovable things.

Looking out for sorrow,

slowing down for happiness,

making all the right turns

right down to the thumping barriers to the sea,

the swirling waves,

the narrow streets, the houses,

the past, the future,

the doorway that belongs

to you and me.

Why we love this poem: she’s very optimistic about the journey of life, and is hoping to come to a happy point in life.

12. A Dream of Trees

“A Dream of Trees,” another of Oliver’s best-known pieces, was included in her debut poetry collection, No Voyage and Other Poems (1963). The speaker of this poem describes one of her dreams, which is of none other than trees.

She can only find peace in dreams that have no connection to reality. The causes are clear; the important ones are increasing consumption, rapid urbanization, deforestation, and death.

There is a thing in me that dreamed of trees,

A quiet house, some green and modest acres

A little way from every troubling town,

A little way from factories, schools, laments.

I would have time, I thought, and time to spare,

With only streams and birds for company,

To build out of my life a few wild stanzas.

And then it came to me, that so was death,

A little way away from everywhere.

There is a thing in me still dreams of trees.

But let it go. Homesick for moderation,

Half the world’s artists shrink or fall away.

If any find solution, let him tell it.

Meanwhile I bend my heart toward lamentation

Where, as the times implore our true involvement,

The blades of every crisis point the way.

I would it were not so, but so it is.

Who ever made music of a mild day?

13. The Journey

Oliver’s most well-known poem is “The Journey,” a free-verse composition. This poem tells the story of one speaker’s trek into nature to escape the tight grips of her loved ones. The sounds in the area were luring her away, but she was aware of what had to be done and what would be the best course of action to save the “sole life” that was preserving humanity.

One day you finally knew

what you had to do, and began,

though the voices around you

kept shouting

their bad advice —

though the whole house

began to tremble

and you felt the old tug

at your ankles.

“Mend my life!”

each voice cried.

But you didn’t stop.

You knew what you had to do,

though the wind pried

with its stiff fingers

at the very foundations,

though their melancholy

was terrible.

It was already late

enough, and a wild night,

and the road full of fallen

branches and stones.

But little by little,

as you left their voice behind,

the stars began to burn

through the sheets of clouds,

and there was a new voice

which you slowly

recognized as your own,

that kept you company

as you strode deeper and deeper

into the world,

determined to do

the only thing you could do —

determined to save

the only life that you could save.

14. In Blackwater Woods

“In Blackwater Woods,” one of Mary Oliver’s most well-known and often cited poems, was first released in her fifth book, American Primitive (1983), which won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

This free-verse poem is inspired by the Province Lands’ Blackwater Woods, which surround an unnamed freshwater pond in Provincetown, Massachusetts’s Cape Cod National Seashore.

Look, the trees

are turning

their own bodies

into pillars

of light,

are giving off the rich

fragrance of cinnamon

and fulfillment,

the long tapers

of cattails

are bursting and floating away over

the blue shoulders

of the ponds,

and every pond,

no matter what its

name is, is

nameless now.

Every year

everything

I have ever learned

in my lifetime

leads back to this: the fires

and the black river of loss

whose other side

is salvation,

whose meaning

none of us will ever know.

To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it

go,

to let it go.

15. Morning

Another beautiful poem from Oliver’s New and Selected Poems, winner of the National Book Award (1992). In “Morning,” the poet spends a beautiful morning contemplating the little items in her chilly kitchen and observing the motions of her black cat. This essay explores her surprise at the amazing things in her little environment.

Every morning

the world

is created.

Under the orange

sticks of the sun

the heaped

ashes of the night

turn into leaves again

and fasten themselves to the high branches–

and the ponds appear

like black cloth

on which are painted islands

of summer lilies.

If it is your nature

to be happy

you will swim away along the soft trails

for hours, your imagination

alighting everywhere.

And if your spirit

carries within it

the thorn

that is heavier than lead–

if it’s all you can do

to keep on trudging–

there is still

somewhere deep within you

a beast shouting that the earth

is exactly what it wanted–

each pond with its blazing lilies

is a prayer heard and answered

lavishly,

every morning,

whether or not

you have ever dared to be happy,

whether or not

you have ever dared to pray.

16. White-Eyes

One of Mary Oliver’s winter poems is this one. A clever but straightforward poem on the arctic wind is “White-Eyes.” It is described as a white-feathered bird that summons the clouds from the north in the speaker’s imagination.

The wind-bird then goes to sleep as it starts to snow. The poems were initially published in Poetry’s October-November 2002 edition. Read this lovely article about snow below:

In winter

all the singing is in

the tops of the trees

where the wind-bird

…

with its white eyes

shoves and pushes

among the branches.

Like any of us

…

he wants to go to sleep,

but he’s restless—

he has an idea,

and slowly it unfolds

…

from under his beating wings

as long as he stays awake.

But his big, round music, after all,

is too breathy to last.

…

So, it’s over.

In the pine-crown

he makes his nest,

he’s done all he can.

…

I don’t know the name of this bird,

I only imagine his glittering beak

tucked in a white wing

while the clouds—

…

which he has summoned

from the north—

which he has taught

to be mild, and silent—

…

thicken, and begin to fall

into the world below

like stars, or the feathers

of some unimaginable bird

…

that loves us,

that is asleep now, and silent—

that has turned itself

into snow.

17. Reckless Poem

This poem’s “recklessness” comes not from the choice of words but from the poet’s carelessness in trying to blend in with nature and other animals. She is not herself when she is out there. When she comes upon anything life, she merges with it:

Just yesterday I watched an ant crossing a path, through the

tumbled pine needles she toiled.

And I thought: she will never live another life but this one.

And I thought: if she lives her life with all her strength

is she not wonderful and wise?

And I continued this up the miraculous pyramid of everything

until I came to myself.

…

And still, even in these northern woods, on these hills of sand,

I have flown from the other window of myself

to become white heron, blue whale,

red fox, hedgehog.

Oh, sometimes already my body has felt like the body of a flower!

Sometimes already my heart is a red parrot, perched

among strange, dark trees, flapping and screaming.

18. August

In “August,” another great poetry from American Primitive (1983) anthology, the speaker enjoys the flavorful blackberries in the untamed brambles. She is free to use her “happy tongue” as much as she wants and continuously consume the “black honey of summer.”

When the blackberries hang

swollen in the woods, in the brambles

nobody owns, I spend

all day among the high

branches, reaching

my ripped arms, thinking

of nothing, cramming

the black honey of summer

into my mouth; all day my body

accepts what it is. In the dark

creeks that run by there is

this thick paw of my life darting among

the black bells, the leaves; there is

this happy tongue.

19. Song for Autumn (Mary Oliver Autumn Poems)

Don’t you imagine the leaves dream now

how comfortable it will be to touch

the earth instead of the

nothingness of the air and the endless

freshets of wind? And don’t you think

the trees, especially those with

mossy hollows, are beginning to look for

the birds that will come—six, a dozen—to sleep

inside their bodies? And don’t you hear

the goldenrod whispering goodbye,

the everlasting being crowned with the first

tuffets of snow? The pond

stiffens and the white field over which

the fox runs so quickly brings out

its long blue shadows. The wind wags

its many tails. And in the evening

the piled firewood shifts a little

longing to be on its way.

20. Watering the Stones

Every summer I gather a few stones from

the beach and keep them in a glass bowl.

Now and again I cover them with water,

and they drink. There’s no question about

this; I put tinfoil over the bowl, tightly,

yet the water disappears. This doesn’t

mean we ever have a conversation, or that

they have the kind of feelings we do, yet

it might mean something. Whatever the

stones are, they don’t lie in the water

and do nothing.

Some of my friends refuse to believe it

happens, even though they’ve seen it. But

a few others—I’ve seen them walking down

the beach holding a few stones, and they

look at them rather more closely now.

Once in a while, I swear, I’ve even heard

one or two of them saying “Hello.”

Which, I think, does no harm to anyone or

anything, does it?

Best Mary Oliver Love Poems

1. I KNOW SOMEONE

I know someone who kisses the way

a flower opens, but more rapidly.

Flowers are sweet. They have

short, beatific lives. They offer

much pleasure. There is

nothing in the world that can be said

against them.

Sad, isn’t it, that all they can kiss

is the air.

Yes, yes! We are the lucky ones.

2. HOW DO I LOVE YOU?

How do I love you?

Oh, this way and that way.

Oh, happily. Perhaps

I may elaborate by

demonstration? Like

this, and

like this and

no more words now

3. NOT ANYONE WHO SAYS

Not anyone who says, “I’m going to be

careful and smart in matters of love,”

who says, “I’m going to choose slowly,”

but only those lovers who didn’t choose at all

but were, as it were, chosen

by something invisible and powerful and uncontrollable

and beautiful and possibly even

unsuitable —

only those know what I’m talking about

in this talking about love.

4. I DID THINK, LET’S GO ABOUT THIS SLOWLY

I did think, let’s go about this slowly.

This is important. This should take

some really deep thought. We should take

small thoughtful steps.

But, bless us, we didn’t.

Mary Oliver Nature Poems

1. Hummingbirds

The female, and the two chicks,

each no bigger than my thumb,

scattered,

shimmering

in their pale-green dresses;

then they rose, tiny fireworks,

into the leaves and hovered;

then they sat down,

each one with dainty, charcoal fee—

each one on a slender branch—

and looked at me.

2. Banyan

Something screamed

from the fringes of the swamp.

It was Banyan,

the old merchant.

It was the hundred-legged

tree, walking again.

The cattle egret

moved out into the sunlight,

like so many pieces of white ribbon.

The watersnakes slipped down the banks

like green hooks and floated away.

Banyan groaned.

A knee down in the east corner buckled,

a gray shin rose and the root,

wet and hairy,

sank back in, a little closer.

Then a voice like a howling wind deep in the leaves said:

I’ll tell you a story

about a seed.

About a seed flying into a tree, and eating it

little by little.

3. The Kingfisher

The kingfisher rises out of the black wave

like a blue flower, in his beak

he carries a silver leaf. I think this is

the prettiest world—so long as you don’t mind

a little dying, how could there be a day in your whole life

that doesn’t have its splash of happiness?

There are more fish than there are leaves

on a thousand trees, and anyway the kingfisher

wasn’t born to think about it, or anything else.

When the wave snaps shut over his blue head, the water

remains water—hunger is the only story

he has ever heard in his life that he could believe.

4. The Mango

One evening I met the mango.

At first there were four or five of them

in a bowl.

They looked like stones you find

in the rivers of Pennsylvania

when the waters are low.

That size, and almost round.

Mossy green.

But this was a rich house, and clever too.

After salmon and salads

mangoes for everyone appeared on blue plates,

each one cut in half and scored

and shoved forward from its rind, like an orange flower,

cubist and juicy.

When I began to eat

things happened.

All through the sweetness I heard voices,

men and women talking about something—

another country, and trouble.

It wasn’t my language, but I understood enough.

Jungles, and death. The ships

leaving the harbors, their holds

filled with mangoes.

5. The Moths

There’s a kind of white moth, I don’t know

what kind, that glimmers

by mid-May

in the forest, just

as the pink moccasin flowers

are rising.

If you notice anything,

it leads you to notice

more

and more.

And anyway

I was so full of energy.

I was always running around, looking

at this and that.

If I stopped

the pain

was unbearable.

Mary Oliver Mother Poem

Flare by Mary Oliver

1.

Welcome to the silly, comforting poem.

It is not the sunrise,

which is a red rinse,

which is flaring all over the eastern sky;

it is not the rain falling out of the purse of God;

it is not the blue helmet of the sky afterward,

or the trees, or the beetle burrowing into the earth;

it is not the mockingbird who, in his own cadence,

will go on sizzling and clapping

from the branches of the catalpa that are thick with blossoms,

that are billowing and shining,

that are shaking in the wind.

2.

You still recall, sometimes, the old barn on your

great-grandfather’s farm, a place you visited once,

and went into, all alone, while the grownups sat and

talked in the house.

It was empty, or almost. Wisps of hay covered the floor,

and some wasps sang at the windows, and maybe there was

a strange fluttering bird high above, disturbed, hoo-ing

a little and staring down from a messy ledge with wild,

binocular eyes.

Mostly, though, it smelled of milk, and the patience of

animals; the give-offs of the body were still in the air,

a vague ammonia, not unpleasant.

Mostly, though, it was restful and secret, the roof high

up and arched, the boards unpainted and plain.

You could have stayed there forever, a small child in a corner,

on the last raft of hay, dazzled by so much space that seemed

empty, but wasn’t.

Then–you still remember–you felt the rap of hunger–it was

noon–and you turned from that twilight dream and hurried back

to the house, where the table was set, where an uncle patted you

on the shoulder for welcome, and there was your place at the table.

3.

Nothing lasts.

There is a graveyard where everything I am talking about is,

now.

I stood there once, on the green grass, scattering flowers.

4.

Nothing is so delicate or so finely hinged as the wings

of the green moth

against the lantern

against its heat

against the beak of the crow

in the early morning.

Yet the moth has trim, and feistiness, and not a drop

of self-pity.

Not in this world.

5.

My mother

was the blue wisteria,

my mother

was the mossy stream out behind the house,

my mother, alas, alas,

did not always love her life,

heavier than iron it was

as she carried it in her arms, from room to room,

oh, unforgettable!

I bury her

in a box

in the earth

and turn away.

My father

was a demon of frustrated dreams,

was a breaker of trust,

was a poor, thin boy with bad luck.

He followed God, there being no one else

he could talk to;

he swaggered before God, there being no one else

who would listen.

Listen,

this was his life.

I bury it in the earth.

I sweep the closets.

I leave the house.

6.

I mention them now,

I will not mention them again.

It is not lack of love

nor lack of sorrow.

But the iron thing they carried, I will not carry.

I give them–one, two, three, four–the kiss of courtesy,

of sweet thanks,

of anger, of good luck in the deep earth.

May they sleep well. May they soften.

But I will not give them the kiss of complicity.

I will not give them the responsibility for my life.

7.

Did you know that the ant has a tongue

with which to gather in all that it can

of sweetness?

Did you know that?

8.

The poem is not the world.

It isn’t even the first page of the world.

But the poem wants to flower, like a flower.

It knows that much.

It wants to open itself,

like the door of a little temple,

so that you might step inside and be cooled and refreshed,

and less yourself than part of everything.

9.

The voice of the child crying out of the mouth of the

grown woman

is a misery and a disappointment.

The voice of the child howling out of the tall, bearded,

muscular man

is a misery, and a terror.

10.

Therefore, tell me:

what will engage you?

What will open the dark fields of your mind,

like a lover

at first touching?

11.

Anyway,

there was no barn.

No child in the barn.

No uncle no table no kitchen.

Only a long lovely field full of bobolinks.

12.

When loneliness comes stalking, go into the fields, consider

the orderliness of the world. Notice

something you have never noticed before,

like the tambourine sound of the snow-cricket

whose pale green body is no longer than your thumb.

Stare hard at the hummingbird, in the summer rain,

shaking the water-sparks from its wings.

Let grief be your sister, she will whether or no.

Rise up from the stump of sorrow, and be green also,

like the diligent leaves.

A lifetime isn’t long enough for the beauty of this world

and the responsibilities of your life.

Scatter your flowers over the graves, and walk away.

Be good-natured and untidy in your exuberance.

In the glare of your mind, be modest.

And beholden to what is tactile, and thrilling.

Live with the beetle, and the wind.

This is the dark bread of the poem.

This is the dark and nourishing bread of the poem.

Mary Oliver Poem About Friendship

What is the greatest gift?

What is the greatest gift?

Could it be the world itself — the oceans, the meadowlark,

the patience of the trees in the wind?

Could it be love, with its sweet clamor of passion?

Something else — something else entirely

holds me in thrall.

That you have a life that I wonder about

more than I wonder about my own.

That you have a life — courteous, intelligent —

that I wonder about more than I wonder about my own.

That you have a soul — your own, no one else’s —

that I wonder about more than I wonder about my own.

So that I find my soul clapping its hands for yours

more than my own.

Read more:

FAQs

Who is Mary Oliver?

Mary Oliver is an American poet, essayist, and naturalist. She has published more than 15 collections of poetry and won many awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1984.

What are some themes in Mary Oliver’s poems?

Some common themes in Mary Oliver’s poetry include nature, love, death, and transcendence. She often uses the natural world as a metaphor for her own inner life and spiritual journey.

What is the style of Mary Oliver’s poems?

Mary Oliver’s poetry is known for its use of simple language and imagery to explore complex emotions and ideas. Her poems are often written in free verse and focus on nature and spirituality.

Conclusion

Mary Oliver’s poems are a testament to the beauty and power of nature. They capture the essence of life and death, love and loss, and all of the other experiences that make up our lives. Her poetry is a reminder to appreciate the wonders of the world around us and the importance of living life fully. Mary Oliver’s poetry will continue to inspire readers for generations to come.